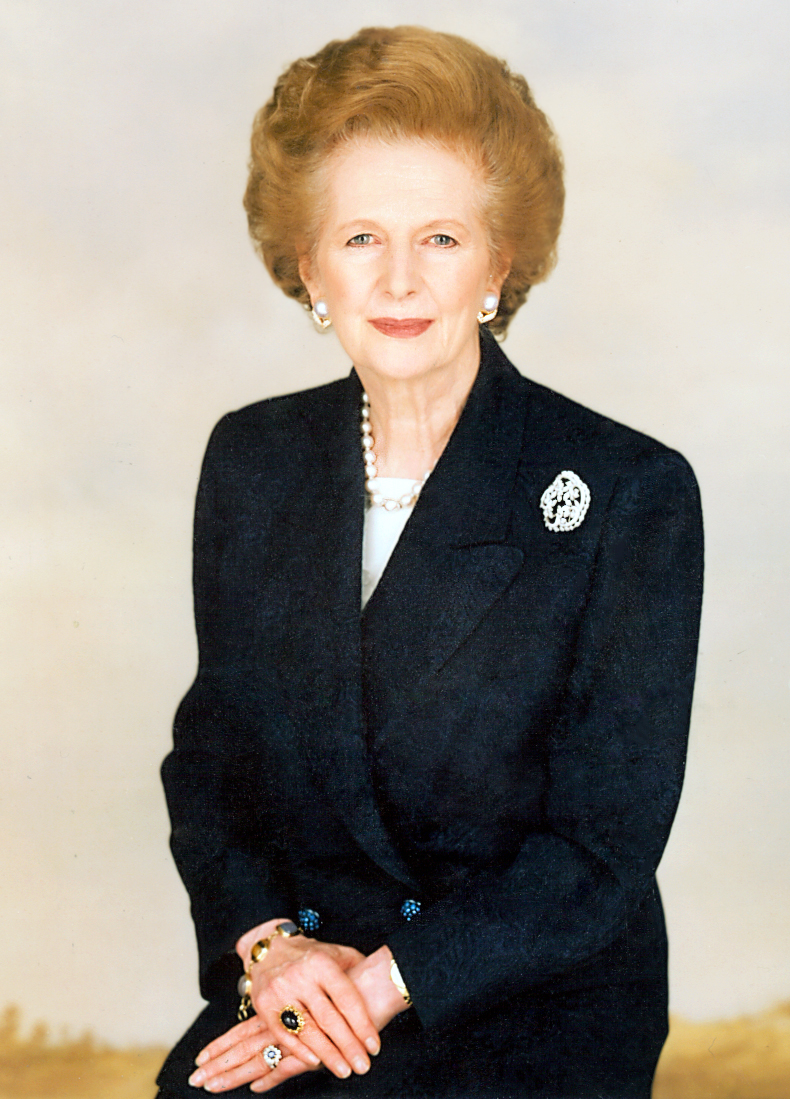

Margaret Thatcher: Iron Lady or Attila the Hen?

- Jan 14, 2022

- 6 min read

Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher, would undoubtedly be one of the top choices if anyone were to compile the most polarizing figure of recent history. On one hand, she’s a feminist icon who finally broke the stubborn trend of male leaders in the U.K. by becoming its first female Prime Minister. Thatcher is also credited with moving the stagnating English economy of the 1970s towards a deregulated, privatized free-market system, called Thatcherism, which allowed the region to return to its former glory. On the other hand, she is criticized for the abrupt sectoral shift in England that favoured the entrepreneurial South over the industrial North, causing mass unemployment, the end of vital manufacturing industries, and the loss of trade union power in England, particularly in the North where mass inner-city riots and the Coal Miners’ Strike of 1984 were notable representations of dissent towards her regime. Although contemporary economists deem her to be the ‘Iron Lady’ of England who revolutionized its economy and made the nation a major world power, historians at the Historical Writers’ Association (HWA) recently crowned her as the ‘Worst British Prime Minister of the Last Century’ - through a poll that determined her to be worse than former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who ‘appeased’ Adolf Hitler by relinquishing Czechoslovakia to the Nazis.

What were Thatcher’s Most Respected/Controversial Policies?

PRIVATISATION, SECTORAL SHIFT, AND THE ECONOMY:

Margaret Thatcher was notable for her penchant for capitalism and deregulation. From the very start of her premiership, free-market reforms took a forefront in her economic policy that was entrenched in a struggle to remedy the 1979-1981 recession; these reforms entailed an increase in interest rates and Value-Added Tax (VAT) rates to bring down inflation. They resulted in over 10,000 businesses declaring bankruptcy and over 3 million workers becoming unemployed, which all boiled over to form the Brixton Riot of 1981. Despite her surprising success in reviving economic growth by 1982, the high unemployment levels that persisted until 1987 would significantly mar Thatcher’s premiership and legacy as they began the manufacturing sector’s decline, with manufacturing output dropping by 30% as early as 1983.

The second wave of reforms began as soon as she was re-elected in 1983 when state-owned industries, such as steel, gas, electricity and water, and council houses were sold to private investors, amassing 37 billion pounds of government earnings. Moreover, deregulation of the stock market and financial institutions in 1986, known as the ‘Big Bang’, led to a flood of foreign investment into the economy, strengthening foreign currency reserves and creating more jobs in the long run. Privatization allowed inflation rates to reduce further, making goods cheaper for consumers but also enabled unemployment levels to remain high as private firms were less willing to employ unskilled and unproductive workers than the government.

The most violently received reform was, however, Thatcher’s ban on trade unions in 1984. According to the Prime Minister, trade unions took control of industries and workers away from the state and caused economic chaos through strikes and protests. Trade unions were a vital part of the U.K.’s main industries as they ensured rights for workers and fair wage rates. Thus, this ban reduced job security for industrial and manufacturing sector workers further amidst persistently high unemployment levels, prompting strikes and riots. Most notable among these was the Coal Miners’ Strike during which two-thirds of the country’s coal miners went on strike from March 1984 to March 1985, protesting the government’s decision to shut down 20 state-owned mines and cut almost 20,000 jobs. The government did not yield as Thatcher was adamant about using police brutality to quell protests, comparing miners on strike to the Argentinians who were at war with the British at the time (Falklands War):

“We had to fight the ‘enemy without’ in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the ‘enemy within’, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty.”

When the miners eventually conceded, the economy had suffered a loss of output amounting to around 1.5 billion pounds and a significant drop in the pound’s exchange rate. Subsequently, trade unions were suppressed further and more mines were closed, crippling entire communities that had relied on the tens of thousands of mining jobs that had been cut. The decline of manufacturing industries that resulted is an example of a sectoral shift, whereby an economy shifts from the manufacturing sector to service-based sectors. Since manufacturing industries were concentrated in the North of England, this sectoral shift led to the economic decline and decay of the North as the balance of economic strength shifted towards the educated and entrepreneurial South.

Peter Tatchell, a political activist, told Al Jazeera. “She pursued policies that caused great suffering to millions of ordinary working-class men and women in this country. She decimated the manufacturing base, causing unprecedented mass unemployment. She used virtual police state methods to suppress the miners’ strike. The miners were effectively starved back to work. These were very cruel and heartless policies.”

David Hopper, the general secretary of the Durham Miners Association explained, “Our children have got no jobs and the community is full of problems. There’s no work and no money and it’s very sad the legacy she has left behind. She absolutely hated working people and I have very bitter memories of what she did. She turned all the nation against us and the violence that was meted out on us was terrible.”

Nevertheless, contemporary economists have argued that the impact of these job cuts was off-set by privatization. When industries are privatized, the investors and firms that own them have a profit motive and long-term expansionary ambitions, unlike the government. This prompts job creation in the same industries that faced job cuts, reducing pressure on the government to create jobs. At the same time, unemployment benefits were made more abundant as government earnings increased with the sale of state-owned industries. However, not everyone was compensated as some workers, particularly the elderly, were seen as undesirable or unskilled for the newly privatized industries, leaving them disadvantaged.

FOREIGN POLICY:

Although the Falklands War has been mocked in recent years, it was, at the time, a major contributor to the extension of Thatcher’s premiership. The Falklands War began in 1982 when Argentina’s military dictator, Leopoldo Galtieri, ordered the invasion of the British-ruled Falklands Islands and South Georgia Islands that were located near the Southern Argentine coast. British victory in this war, achieved within a few months, is credited as one of the main reasons for Thatcher’s re-election in 1983. However, the opposition came to brandish the conflict as a weapon, citing that Thatcher was too entrenched in her economic reforms to prevent the invasion. Yet, it undoubtedly raised people’s opinions of the Prime Minister as opinion polls came to be in favour of her, while military prestige also rose after the Falklands victory, enabling British participation in wars in Afghanistan, the Gulf, and Iraq in the years that followed.

However, Thatcher earned a bitter reputation among anti-apartheid South Africans and humanitarian activists when she opposed European sanctions on South Africa and accused Nelson Mandela of being a “terrorist "to maintain favourable trade relations with South Africa’s apartheid regime in 1984. Even though she claimed to support efforts to dismantle the apartheid regime, her actions inevitably made her responsible for delays in the fall of the South African apartheid regime.

NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE TROUBLES:

Prime Minister Thatcher faced backlash in 1981 when she refused to yield to the demands of Bobby Sands and Irish Unionist army (PIRA and INLA) members, jailed in English-governed Northern Ireland, who had gone on hunger strike for better prisoner living conditions. She was famously quoted to have apathetically replied, “Crime is a crime is a crime; it is not political.” As a result, Sands and nine other inmates died, leading to escalations in violence in Northern Ireland.

In retaliation, the Irish Republican Army led an assassination attempt on Thatcher in 1984. The Prime Minister narrowly escaped the attack, but five others lost their lives in the ordeal. Subsequently, in an effort for peace, Thatcher met with the Irish Taoiseach FitzGerald to sign the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, signifying the first instance of British governance making a compromise with the Republic of Ireland over the governance of Northern Ireland. However, Ulster representatives from the ‘Ulster Says No’ campaign protested the Agreement, amassing a crowd of over 100,000 in Belfast in response. Tensions continued afterwards, but Thatcher’s willingness to make peace, instead of retaliate after the assassination attempt, has been commended by many, who also suggest that it laid the foundations for the Good Friday Peace Agreement of 1998.

How Can You Help?

The best way to analyse and learn from Margaret Thatcher’s policies is to read up on them. Examining the successes and failures of former leaders helps the next generation learn from their mistakes to bring about more pragmatic and efficient changes in the future. Having accurate and detailed knowledge on various outside perspectives of a leader’s life may also benefit you.

Sources and References:

Comments